The year is 1569, and in the hallowed surroundings of Durham Cathedral, something earth-shattering is taking place: they are singing Mass. Perhaps this is not especially significant in itself – after all, Mass was sung every day in that cathedral for four centuries. But this is Elizabethan England. For ten years Mass has been outlawed, and now, saying those words, once so revered, is treason and heresy. That such a dangerous act is taking place in one of England’s most ancient and respected churches could spell the end of everything Elizabeth I and her council have ever stood for.

This was the call-to-arms of the Northern Rebellion, a movement that swept across the North of England in 1569, led by the Earl of Westmorland, Charles Neville, and Thomas Percy, the Earl of Northumberland. Both were Catholics, and in their lands, two hundred miles from London, the people had yet to be convinced by Elizabeth’s changes to religious policy. Rumours of insurrection in the North reached crisis point in November 1569 and Elizabeth summoned Westmorland and Northumberland to her northern council at York. Seizing their opportunity, the Earls reacted immediately. They and their co-conspirators marched on Durham, replaced the Protestant communion tables with altars, and reinstated the old Catholic services: the Mass, the Office, and the votive Marian antiphon. Immediately, the Catholic public in the North raced to join them. Marching under the ancient banner of the English Crusaders, they besieged Barnard Castle and Hartlepool and sacked the palace of the Bishop of Durham, singing Masses wherever they went. It could have spelt the end for the Elizabethan establishment.

When Northumberland was arrested and questioned he claimed that the rebels had had three aims: to remove Elizabeth’s Protestant council and replace them with Catholics; to reverse the religious settlement of 1559; and to persuade Elizabeth to name her Catholic cousin Mary, Queen of Scots, who had recently been forced to abdicate and seek refuge in England, as her heir and successor. He insisted that they had never intended treason – they never objected to the Queen’s divinely imposed rule. Rather, they were fighting against her corrupt councillors who had led her astray from the true Catholic Church. The rebels’ rallying-cry to their people had made this the very centre of their claims:

‘Thomas, earl of Northumberland and Charles, earl of Westmorland, the Queen’s most true and lawful subjects, and to all her highness’s people, sendeth greeting: Whereas diverse new set up nobles about the Queen’s Majesty, have and do daily, not only go about to overthrow and put down the ancient nobility of this realm, but also have misused the Queen’s Majesty’s own person, and also have by the space of twelve years now past, set up and maintained a newfound religion and heresy, contrary to God’s word. […] These are therefore to will and require you, and every of you, being above the age of sixteen years and not sixty, as your duty to God doth bind you, for the setting forth of His true and catholic religion; and as you tender the common wealth of your country, to come and resort unto us with all speed, with such armour and furniture as you, or any of you have. […] God save the Queen.’ (Kesselring 2010: 59)

It wasn’t just fighting and strong words, though, with which the rebels presented their cause. They went further than that: their opinions were presented in music and art as well. I’ll talk about two examples here.

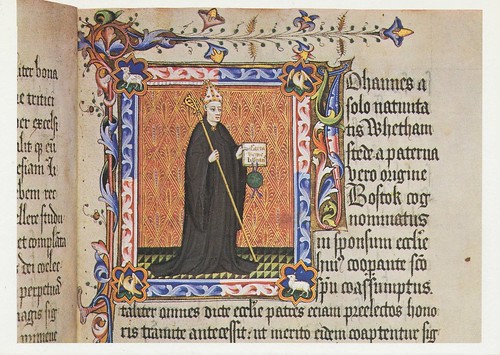

Statements made by many of the cathedral singing-men still survive, and we know the names of many who sang at the newly reinstated Catholic services. We know from John Brimley and Thomas Harrison’s testaments that the Earl of Northumberland and Cuthbert Neville both ordered that the Mass should be sung, rather than said – this would have only enhanced the sensory impact that the Mass created. (Depositions and other ecclesiastical proceedings from the courts of Durham, extending from 1311 to the reign of Elizabeth [1845]: 149, 152) One of the prebendaries, George Cliffe, gave even more detail. He said that ‘on Saturdaye, the said thirde day of December, he, this examinate, was at evensonge in Latten, and at singing of the anthem caulde Gaude, Virgo Christopara, upon the said sonndaye [4 December] at night…’ (Depositions: 136). Cliffe was referring to the practice, established long before the Reformation, of singing a Marian antiphon, either Salve Regina or some other devotional text, after Compline as the last service of the day.

Magnus Williamson has pointed out that there is only one possible piece answering to Cliffe’s description: John Sheppard’s Gaude, Virgo Christiphera (‘Rejoice, Virgin, bearer of Christ’) (Williamson 2014: 709). You can listen to the whole piece here. Sheppard had died in 1558 and the piece is very much in the style of the first half of the sixteenth century – it would have seemed outdated to both singers and listeners alike, so a performance of it was a very conscious return to the sound-world of pre-Reformation Catholic England. While obviously we should be wary of reading meanings into Latin texts that tend to use highly stereotyped language and themes, the text of this antiphon is unusually graphic:

Ex te semen hoc divinum From you [came] the divine seed cujus caput serpentinum by whose strength ex contritum viribus […] the head of the serpent is crushed […]

Ergo Sathan mors peccatum Therefore, Satan, death and sin, hinc videtis procreatum you will see him, born ut vestra habens capita. so that he may have dominion over your heads.

The last line translates literally as ‘so that he may have your heads’, but habeo can also mean ‘have’ in the sense of ‘have mastery over’ or ‘possess’ or even ‘enslave’. Capita literally means ‘heads’ but can refer to ‘leaders’ as well. Could the ‘head of the serpent’ and the ‘heads of Satan’ that Christ will overcome be referring to the heretical councillors that the rebels claimed to be overthrowing? And although, unusually, the name Maria is not mentioned, it cannot have been far from the minds of the listeners: the name not only of the ‘bearer of Christ’ in the antiphon’s title, but also of Elizabeth’s Catholic predecessor, and her potential replacement. Just imagine the impact this must have had at the end of a full day of Catholic liturgy, Matins, Mass, Vespers, Compline and the antiphon, all in the most elaborate style, at a time when most of those present would still remember a time when all this was just a matter of course. It must have been at once exhilarating and baffling to see the past – their past – brought before them once again, in sight, sound and smell, with the opportunity not only to witness but also participate in worship in the ways they had learned as children.

In a period when even speculating about the monarch’s death was a treasonous act, a musical performance implicitly connecting her policies with ‘Sathan, mors, peccatum‘ could be political dynamite. And if the performance of a song – a mere pattern of sounds that survives only as hearsay – was powerful, a piece of art that has endured for more than four and a half centuries must be infinitely more so.

Sizergh Castle, near Kendal in the old county of Westmorland, has been the seat of the Strickland family since the fourteenth century. There’s no evidence at the moment that they took part in the rebellion, but we know that they were following it closely. Walter Strickland, the owner of Sizergh who died in 1569, was considered to be a good Protestant, but his son Thomas was a Catholic recusant and later on his descendants supported the Royalist side in the Civil War. Just before he died, Walter embarked on a refurbishment of Sizergh, which includes perhaps the greatest statement of both his, and his son’s, religious and political views at the same time. How can this be? Well, here it is. This drawing room is called the Queen’s Room, and takes its name from the carved overmantel which bears the coat of arms of Queen Elizabeth and the date 1569.

(For this and other pictures of Sizergh, visit the National Trust website here)

(For this and other pictures of Sizergh, visit the National Trust website here)

(An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Westmorland (London, 1936), p. 104 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/westm/plate-104 [accessed 12/2/15].)

(An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Westmorland (London, 1936), p. 104 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/rchme/westm/plate-104 [accessed 12/2/15].)

This carving, which was begun by Walter and completed by his son, is a wonderfully ambiguous statement. Created amid rising tension in the North in the months leading up to the Rebellion, it proclaims the Stricklands’ loyalty to the Queen for all their most honoured guests to see. It says that yes, the other families in their area might rebel, but they wouldn’t dream of such a thing. On another level though – and perhaps this is why Thomas Strickland kept it – it covertly demonstrates support for the Northern Earls. After all, they’d said it wasn’t Elizabeth they were fighting, but her corrupt councillors. They were the Queen’s true loyal subjects, saving her from her treasonous council’s dangerous influence. Of course all these excuses were extremely tongue-in-cheek, but they mean that despite having been first made for Thomas’s conformist father, the overmantel is in no way incompatible with Thomas’s identity as an English Catholic.

In fact, it had the potential to do him a lot of good. The nature of this room means that Thomas could carefully gauge how he presented himself to his visitors. It’s largely inaccessible from the more public areas of the house, so anybody seeing it would have been invited in as a great honour. Anybody who might disapprove of Thomas’s religion could be invited into this intimate space, with great show of deference and respect, and be confronted with what appeared to be Thomas’s assurance of his religious and political orthodoxy.

Politics in the North of England in 1569, then, wasn’t just about marching, fighting, waving banners, or even about treasonous whispers in the dark. It was a time when achieving outward conformity was a matter of life and death, and when a person’s every action betrayed their political allegiance. In such an atmosphere, the liturgical performance of Gaude Virgo Christiphera can be read as a piece of public theatre, communicating the message of rebellion against Elizabeth’s regime in a way that had the power to engage everybody present in every possible way. And an at-first-glance innocuous piece of interior design can be read as both a gesture of loyalty, a last-ditch attempt at self-defence, or a subtle hint to fellow Catholics, whose meaning shifts according to the observer.

Select Bibliography:

Alford, Stephen. The Watchers: A Secret History of the Reign of Elizabeth I (New York: Bloomsbury, 2012).

Kesselring, K. J. The Northern Rebellion of 1569: Faith Politics and Protest in Elizabethan England (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010).

Kesselring, K. J. ‘”A Cold Pye for the Papistes”: Constructing and Containing the Northern Rising of 1569’ Journal of British Studies 43 (2004), 417-443.

National Trust. Sizergh Castle, Cumbria (London: National Trust, 2001). (PS. This is the guidebook that you can buy from the Castle!)

Williamson, Magnus. Review: ‘Church Music and Protestantism in Post-Reformation England: Discourses, Sites and Identities, by Jonathan Willis (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010; pp. 294. £55.).’ English History Review 124 (2014), 707-709.

Willis, Jonathan P. Church Music and Protestantism in Reformation England: Discourses, Sites and Identities (Farnham: Ashgate, 2010).

Depositions and other ecclesiastical proceedings from the courts of Durham, extending from 1311 to the reign of Elizabeth (London and Edinburgh: 1845); https://archive.org/details/otherdepositions00churrich (accessed 12/2/15).

‘STRICKLAND, Walter (c. 1516-69), of Sizergh, Westmld. and Thornton Bridge, Yorks.’ http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1558-1603/member/strickland-walter-1516-69 (accessed 12/2/15).

(An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Westmorland (London, 1936), p. 104

(An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in Westmorland (London, 1936), p. 104